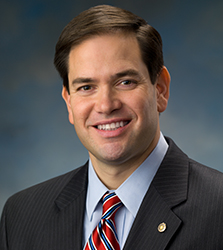

How Long Can Rubio Wait for a Win?

Florida Sen. Marco Rubio has been considered a leading candidate for the GOP nomination for several months, despite not leading or even polling in second place nationally, in Iowa, or in New Hampshire (he has been in second place in South Carolina for about a month and a half, barely ahead of a tangle of other candidates and well behind businessman Donald Trump). The question in many minds has been, when and where does Rubio have to finally win a primary or caucus to confirm his status? Stu Rothenberg in Roll Call offers some thoughts:

Can Rubio Win Even If He Loses?

Can a candidate win the Republican presidential nomination without winning one of the first three contests – Iowa, New Hampshire or South Carolina? We may just find out this year.

This cycle, Florida Sen. Marco Rubio may need to survive a series of early losses before he can emerge as a frontrunner for his party’s nomination. While he is a favorite of pragmatic conservatives, Rubio has yet to consolidate support from the establishment, and some GOP strategists are scratching their heads over his strategy, which they regard as risky.

Critics equate Rubio’s general approach to the nomination calendar – which downplays the Florida senator’s need to “win” a February contest as long as he runs “competitively” – to the strategy employed by former New York City Mayor Rudy Giuliani in 2008.

The Giuliani comparison breaks apart in several ways, as the article points out – the former New York City mayor was a pro-choice moderate out of tune with the caucus-goers and primary voters of the early states, while Rubio’s conservative credentials aren’t in dispute other than possibly on immigration (and those pesky sugar subsidies). But what happened to that ill-fated campaign is worth remembering:

Giuliani … never had a decent showing. He finished far back in the 2008 Michigan and South Carolina primaries, drawing less than 3 percent of the vote in each, and in the Nevada caucuses, drawing 4.3 percent of the vote. Those results followed the former mayor’s sixth-place showing in Iowa and his distant fourth-place finish in New Hampshire.

Making matters worse for Giuliani was that Arizona Sen. John McCain, a pragmatist, won both New Hampshire and South Carolina, and finished second in Michigan. After the first five contests, Giuliani had one delegate to McCain’s 39 delegates.

Because of that, pragmatic Republicans in Florida in 2008 didn’t need an alternative when their primary rolled around. McCain had established himself as the favorite. Giuliani became an after-thought, finishing a distant third in Florida, with 14.7 percent of the vote, far behind McCain’s 36 percent and Romney’s 31 percent.

As Rothenberg points out, Rubio is competing in all the early states while not pinning his campaign’s survival on a first- or second-place finish in any of them. Assuming he isn’t surpassed as the “establishment” candidate by one of the other contenders (former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush, New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie, or Ohio Gov. John Kasich), then he’s probably going to last far into the nominating process, according to Rothenberg:

Polling shows Rubio broadly acceptable within the GOP and a formidable general election nominee. Given that, and considering the size and make-up of the field, his caucus and primary calendar strategy seems reasonable.

Of course, that certainly does not assure him of being in his party’s “finals,” or of convincing a majority of GOP delegates in Cleveland that he is the man to take on Hillary Clinton. But at the very least, it means he is not recycling Giuliani’s failed strategy.

Eventually Rubio would need to start winning, of course, and his home-state primary on March 15 is almost certainly a must-win, but before that it’s not clear he absolutely needs to win anything. Ironically, winning Florida was what Giuliani needed as well.