Democratic Debates Becoming a Non-Factor

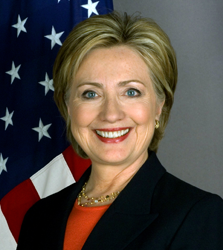

The Democrats held their third debate presidential nomination debate on Saturday night, featuring former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, former Maryland Gov. Martin O’Malley, and Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders. The general view seems to be that nobody did much of anything to change the race. Here’s Politico’s Glenn Thrush:

5 takeaways from the Democratic debate

Sanders — with a powerhouse fundraising operation and widespread appeal among college-age supporters — remains a significant factor in the Democratic primary, but he did little to repulse Clinton’s surge at the dawn of 2016. If there was any question about the Democratic pecking order, it was erased when Clinton returned late from a commercial break — leaving her empty podium to upstage the two men who soldiered on unsuccessfully as the audience focused more on her blaring absence than their uttered eloquences….

Sanders — famously allergic to debate prep and resistant to attacking his opponents on issues not directly pertaining to his core message of income inequality — clearly understood the fierce urgency of knocking Clinton down a peg. But his heart wasn’t quite into it. His staff defiantly refused to apologize for improperly tapping Clinton’s secret voter file, but he quickly offered a mea culpa. "Yes, I apologize," he said. "Not only do I apologize, I want to apologize to my supporters."

That’s not to say he didn’t take his shots. His most effective attack on Clinton, not surprisingly, came when he hammered the former New York senator on her close financial ties to Wall Street.

It speaks well of Sanders as a person, but he needs to recover lost ground.

Over at National Journal Patrick Reis offers up his view that the rhetorical confrontation between frontrunner Clinton and Sanders, her top challenger, is likely to remain closer to tepid than white-hot:

If a face-to-face throwdown full of personal attacks was ever in the cards, they would be on the table already. Both candidates have now had a chance to go for a crushing personal attack—and both not only passed, they came to their rival’s aid: Sanders waived away Clinton’s private email server, Clinton dismissed the Sanders campaign’s data peek as a nonissue….

What accounts for the lack of personal animus?

In short: Sanders can’t win with personal attacks, and Clinton can win without them.

For Sanders, it may be that he just can’t bring himself to use the tactics that resemble those of a standard campaign. Or it may be that he knows that many of his supporters are with him specifically because he doesn’t resemble a standard campaign. He promised not to go negative, he swore off super PACs, and he has built his campaign around support for a specific set of policy positions. If he strays too far from that, he risks losing the luster of idealism that pulls supporters to him to begin with. (It’s not for nothing that, immediately after apologizing to Clinton, Sanders offered a second apology, this time to his supporters, telling them it was not the kind of campaign tactic he supported.)

Similarly, Clinton has little to gain from attempting to bury Sanders by undercutting his character. She’s still the clear favorite to win the party’s nomination, and after a summer in which Sanders put a scare into her camp with some solid poll numbers, she again appears well on her way to a primary win. After that, she’ll need support from the liberal base that’s backing Sanders when she gets to the general election. That doesn’t just mean votes, it also means convincing people to volunteer, organize, and donate with the same vigor that they’re now doing for Sanders. And when Clinton asks Sanders’s followers for their zealous support, she’ll have a much better chance of getting it if she defeats their candidate without demonizing him.

Instead of personal attacks, they’re both taking a safer route, one that protects Sanders’ movement and Clinton’s general election prospects. And that means sparring (sometimes politely, sometimes less so) over policy.

The hesitation on both candidates’ parts to aggressively engage in attacking each other is likely to make the debates on the Democratic side mostly a non-factor in terms of influencing the nomination, at least if both Clinton and Sanders continue their current debate strategies. Another reason why the debates may not play a significant role is that they have been scheduled at times when the likely audiences are expected to be small, something the Sanders campaign has complained about. The Washington Post reports:

Presidential hopeful Bernie Sanders said in a television interview that the Democratic National Committee deliberately scheduled debates at times when viewership would be low in an effort to “protect” the party’s front-runner, Hillary Clinton.

The criticism from Sanders followed the third Democratic debate of the 2016 contest, held here on Saturday night, six days before Christmas and at a time of heightened tensions between the Sanders campaign and the DNC over a data-breach controversy….

Sanders also pointed to the timing of the previous Democratic debate, held last month on a Saturday night in Des Moines at a time when the Iowa Hawkeyes were playing football against the Minnesota Golden Gophers.

“In Iowa, do you know when the debate was held?” Sanders said. “It was the night of the big football game in Iowa. Do you think that’s a coincidence?”

The next Democratic debate will be Jan. 17 in South Carolina, the Sunday evening before the Martin Luther King Jr. national holiday, so the audience will probably be reduced because of the three-day weekend. Because of that factor, plus both candidates’ strategies to avoid aggressively confronting the other face-to-face, it’s likely the Sanders campaign will look for another way to catch the frontrunner. The question is, what could that be?